Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Two stories about transparency

The first is one from the Los Angeles Times, entitled "'Error-free' hospitals scrutinized." Here are some excerpts:

California public health officials are scrutinizing hospitals that claim to be error-free, questioning whether nearly 90 facilities have gone more than three years without any significant mistakes in care.

Eighty-seven hospitals — more than 20% of the 418 hospitals covered under a law that took effect in 2007 — have made no reports of medical errors, according to the California Department of Public Health.

The high percentage has raised concerns that errors have gone unreported. Some patient advocates say it is an indication that hospitals are unwilling to police themselves. State officials have given hospitals until Tuesday to verify their records as error-free or to report errors, as required by law.

Next, a report from The Health Foundation in the United Kingdom. Martin Marshall, Clinical Director and Director of Research and Development, and the late Vin McLoughlin, Director of Quality Performance and Analysis, have published a paper called, "How might patients use information comparing the performance of health service providers?" It is on the BMJ website. They note:

There is a growing body of evidence . . . describing what happens when comparative information about the quality of care and the performance of health services is placed in the public domain. The findings from research conducted over the last 20 years in a number of different countries are reasonably consistent and provide little support for the belief that most patients behave in a consumerist fashion as far as their health is concerned. Whilst patients are clear that they want information to be made publicly available, they rarely search for it, often do not understand or trust it, and the vast majority of people are unlikely to use it in a rational way to choose ‘the best provider’. The evidence suggests that the public reporting of comparative data does seem to play a limited role in improving quality but the underlying mechanism is reputational concern on the part of providers, rather than direct market-based competition driven by service users.

. . . How should policy makers, managers and clinicians respond to these findings? Some might be tempted to suggest that we should focus only on those who work in the health service and discount patients as important stakeholders. We believe that this would be wrong. The public has a clear right to know how well their health system is working, irrespective of whether they want to use the information in an instrumentalist way. Improving the relevance and accessibility of the data should be seen as a good thing in its own right and may start to engage a large number of people in the future.

. . . That patients might want to view health as something other than a commodity presents a conceptual as well as a practical challenge to those responsible for designing and producing comparative performance information. We suggest that for the foreseeable future presenting high quality information to patients should be seen as having the softer and longer term benefit of creating a new dynamic between patients and providers, rather than one with the concrete and more immediate outcome of directly driving improvements in quality of care.

Sign congestion

Each one of these signs was likely added for good reason. But, in combination, they are problematic -- too cluttered.

Also, they are not culturally competent. The blue sign on the left has several languages. None of the others do.

Perhaps it is time for a Lean rapid improvement event about our signs.

Monday, November 29, 2010

Is this normal?

The friend who sent me this note is a research fellow at one of the Boston teaching hospitals, so I guess he is more likely than most to do the kind of research he summarizes. Most people would have taken the referral advice offered without question. If they ever did ask to see a different doctor, most would never get past the "need" for asking for "special permission."

Hi Paul,

I had a strange encounter, and I was wondering if you could tell me if this is normal.

A few months ago my primary care physician recommended I see dermatology for my eczema. His clinic recommended the names of two dermatologists within the same health care system. I looked up both dermatologist on healthgrades.com and found that their patients had given them luke-warm reviews. (There were many reviews, so this wasn't a sampling problem). Also, I have been reading the medical literature about eczema, and knew there were a lot of recent advances, so I wanted somebody who had published and was familiar with the research.

I found another dermatologist, Dr. Caroline Kim. Her patients loved her (according to healthgrades.com), she had published articles in dermatology research (from scholar.google.com), and she trained at top institutions: Harvard Medical School and MGH. I made an appointment with her.

I called my PCP and asked for a referral. The receptionist told me Dr. Kim was "out of network" and they would have to ask my PCP for special permission. I thought this was odd because I had Blue Cross PPO insurance (not HMO), so as far as I knew, there was no "out of network".

A month later, my referral had not been sent. I called my PCP again, and asked for them to send it. After I gave her the name and phone number of the dermatologist, this was the conversation.

Receptionist: I am sorry, that is out of network. We will have to check with Dr. X.

Me: What does "out of network" mean? I thought I had PPO insurance.

Receptionist: You won't get the best care if you go out of network.

Me: Is this a [health care system] policy?

Receptionist: We might not know what medications you are prescribed if you go out of network. Your medical records might not get transferred back to our office.

Me: Is this a [heath care system] policy?

Receptionist: Yes.

A week later I had my referral.

It seems like this health care system is using an insurance term -- "out of network" -- to trick patients into going to specialists that work for the same company. Am I wrong?

Sunday, November 28, 2010

En route to True North

"True North" is a key concept in Lean process improvement. It might be viewed as a mission statement, a reflection of the purpose of the organization, and the foundation of a strategic plan.

"True North" is a key concept in Lean process improvement. It might be viewed as a mission statement, a reflection of the purpose of the organization, and the foundation of a strategic plan.Here are illustrative thoughts from two observers:

The "ideal vision" or "True North" is not metrics so much as a sense of an ideal process to strive for. It sets a direction, and provides a way to focus discussion on how to solve the problems vs. whether to try.

If we don't know where we're going, we will never get there. "True North" expresses business needs that must be achieved and exerts a magnetic pull. True North is a contract, a bond, and not merely a wish list.

Lean is inherently the most democratic of work place philosophies, relying on empowerment of front-line staff to call out problems. The definition of True North, however, does not rely on that same democratic approach. Instead, it is established by the leadership of the organization.

At BIDMC, we have been engaged in a slow and steady approach to adoption of Lean. Our actions have been intentionally characterized by "Tortoise not Hare," as we methodically train one another, carry out rapid improvement events, and integrate the Lean philosophy into our design of work. As you have seen on this blog, staff members have come to embrace Lean and have used it in a variety of clinical and administrative settings.

(For more examples, enter "Lean" in the search box above. I have been presenting them here for some time in the hope that they would be useful to those in other hospitals who are thinking of adopting this approach.)

We have intentionally not, until now, tried to define True North, but things have now progressed sufficiently in terms of our application of the Lean philosophy that the organization is crying out for it. This is just as we had hoped. Establishment of True North before this time, i.e., without an understanding of its role, would not have been as useful in our hospital.

So, the clinical and administrative leaders recently met to try to nail this down. The process is not over. Indeed, our Board of Directors has yet to pitch in and offer their thoughts. But, we are far enough along that I thought you would enjoy seeing the draft.

Here it is:

BIDMC will care for patients the way we want members of our own families to be treated, while advancing humanity's ability to alleviate human suffering caused by disease. We will provide the right care in the right environment and at the right time, eliminating waste and maximizing value.

Here is some commentary to help you interpret and deconstruct this. The first sentence is based on the long-standing tradition of our two antecedent institutions, the New England Deaconess Hospital and the Beth Israel Deaconess hospital. The late doctor Richard Gaintner used to refer to the Deaconess as, "A place where science and kindliness unite in combating disease." That could just as well have been applied to the BI. As an academic medical center, our public service mission of clinical care is enhanced by -- and enhances -- our research and education programs. Our mission is to help humanity, not just the people who live in our catchment area.

The second sentence is offered in realization that the Ptolemaic view of tertiary hospitals as the center of the universe is no longer apt (if it ever was!) We need to view ourselves as being in service to primary care doctors, community hospitals, and other community-based parts of the health care delivery system.

On another level, it is also reflective of the fact that society expects us to be more efficient both within our own walls and in cooperation with our clinical partners, adopting approaches to work that do not waste societal resources.

In contradistinction to what I just said about this not being a democratically established statement, I offer our draft to you -- both those within BIDMC and worldwide -- for your criticism and suggestions. I don't know of other places that engage in this form of crowd-sourcing with regard to True North, but readers of this blog are unusually informed about health care matters, and I welcome your observations.

Behind the scenes

Friday, November 26, 2010

Painfully slow

What would prompt that? This New York Times article, citing a forthcoming NEJM study about medical errors in North Carolina. Here's the lede:

Efforts to make hospitals safer for patients are falling short, researchers report in the first large study in a decade to analyze harm from medical care and to track it over time.

The study, conducted from 2002 to 2007 in 10 North Carolina hospitals, found that harm to patients was common and that the number of incidents did not decrease over time. The most common problems were complications from procedures or drugs and hospital-acquired infections.

Other excerpts:Dr. Landrigan’s team focused on North Carolina because its hospitals, compared with those in most states, have been more involved in programs to improve patient safety.

But instead of improvements, the researchers found a high rate of problems.. . . The findings were a disappointment but not a surprise, Dr. Landrigan said. Many of the problems were caused by the hospitals’ failure to use measures that had been proved to avert mistakes and to prevent infections from devices like urinary catheters, ventilators and lines inserted into veins and arteries.

And another:

Dr. [Bob] Wachter said the study made clear the difficulty in improving patients’ safety.

“Process changes, like a new computer system or the use of a checklist, may help a bit,” he said, “but if they are not embedded in a system in which the providers are engaged in safety efforts, educated about how to identify safety hazards and fix them, and have a culture of strong communication and teamwork, progress may be painfully slow.”

Exactly right, Bob! What does it take to motivate this profession? What does it take to make process improvement part of medical school and residency training programs.Painfully slow, and painful or worse to patients.

---

Addendum: Dr. Wachter also discusses this study on his blog, here.

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

Things we are grateful for this year

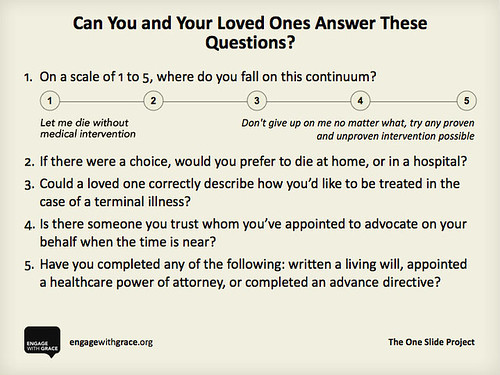

The rally is timed to coincide with a weekend when most of us in the United States are celebrating Thanksgiving and are with the very people with whom we should be having these unbelievably important conversations – our closest friends and family.

At the heart of Engage With Grace are five questions designed to get the conversation about end-of-life started. We have included them at the end of this post. They are not easy questions, but they are important -- and believe it or not, most people find they actually enjoy discussing their answers with loved ones. The key is having the conversation before it’s too late.

This past year has done so much to support our mission to get more and more people talking about their end-of-life wishes. We’ve heard stories with happy endings … and stories with endings that could have (and should have) been better. We have stared down political opposition. We have supported each other’s efforts. And we have helped make this a topic of national importance.

So in the spirit of the upcoming Thanksgiving weekend, we’d like to highlight some things for which we’re grateful.

Thank you to Atul Gawande for writing such a fiercely intelligent and compelling piece on “letting go”– it is a work of art, and a must read.Thank you to whomever perpetuated the myth of “death panels” for putting a fine point on all the things we don’t stand for, and in the process, shining a light on the right we all have to live our lives with intent – right through to the end.

Thank you to TEDMED for letting us share our story and our vision.

And of course, thank you to everyone who has taken this topic so seriously, and to all who have done so much to spread the word, including sharing The One Slide.

We share our thanks with you, and we ask that you share this slide with your family, friends, and followers. Know the answers for yourself, know the answers for your loved ones, and appoint an advocate who can make sure those wishes get honored – it’s something we think you’ll be thankful for when it matters most.

Here’s to a holiday filled with joy – and as we engage in conversation with the ones we love, we engage with grace.

To learn more please go to www.engagewithgrace.org. This post was written by Alexandra Drane and the Engage With Grace team. Please feel free to join our blog rally by copying this post and putting it on your own blog for this holiday weekend.Monday, November 22, 2010

Checklists ain't all

The emphasis on checklists is a Hitchcockian “McGuffan”, a distraction from the plot that diverts attention from how safer care is really achieved. Safer care is achieved when all three—not just one—of the following are realised: summarise and simplify what to do; measure and provide feedback on outcomes; and improve culture by building expectations of performance standards into work processes. We propose that widespread deployment of checklists without an appreciation of how or why they work is a potential threat to patients' safety and to high-quality care.

Sunday, November 21, 2010

Transparency and "dial tone" to fight market power

On the one hand, ACOs offer the potential for a better integration of care across the spectrum of primary care, hospitalization, skilled nursing, rehabilitation, and hospice. If the ACO faces an annual budget per patient under a capitated payment scheme, there is an incentive to avoid unnecessary tests and procedures and also to help direct patients to the most cost-effective component of the health care continuum.

On the other hand, if an ACO becomes the dominant provider in a region and especially if it has a electronic health record that is not interoperable with others in the region, that ACO will have substantial market power and will negotiate a higher global payment than would occur in a more competitive marketplace.

Robert Pear raises similar questions in an article in the New York Times. Here are some excerpts:

[E]ight months into the new law there is a growing frenzy of mergers involving hospitals, clinics and doctor groups eager to share costs and savings, and cash in on the incentives. They, in turn, have deployed a small army of lawyers and lobbyists trying to persuade the Obama administration to relax or waive a body of older laws intended to thwart health care monopolies. . . .

Attorney General Martha Coakley cautioned Friday against a "full-scale push forward" on global payment reform to address spiraling health care costs without addressing the underlying issue of market clout that has led to a disparity in pricing among providers without any clear link to quality of care.

. . . [S]he has directed her staff to resume its effort of examining the health care market in Massachusetts to study models of care delivery and the associated costs.

. . ."A shift to global payments by itself is not the panacea to controlling costs," Coakley said. "Implementing payment reform without addressing the market leverage issue outlined in our report is like trying to fix the roof on a house without fixing the flawed foundation."

Because anti-trust regulatory action is often ineffective against market dominance, we should focus on self-reinforcing policy initiatives to mitigate against this possibility. Here are two suggestions.

The first is one mentioned often on these pages: Total transparency of rates paid by each insurance company to each provider. In Masachusetts, a good first step along these lines was taken by the Legislature and Governor Patrick this past summer. Only when subscribers can see the actual rates being paid will there be the moral force to ensure that rates are reasonably related to factors other than market power.

The second idea is a simple as dial tone: Complete interoperability of medical records among providers. As long as proprietary electronic medical record systems exist, a given provider network can control the degree to which patients can choose lower priced or higher quality doctors and hospitals outside of that network.

Instead, we need the equivalent of the "magic button" described in this post by our CIO, John Halamka, demonstrating interoperability between our hospital and Atrius, the state's largest multi-specialty practice:

By working with Epic and Atrius, we enabled a "Magic Button" inside Epic that automatically matches the patient and logs into BIDMC web-based viewers, so that all Atrius clinicians have one click access to the BIDMC records of Atrius patients.

If this capability existed among and between all provider systems, consumer choice would be possible. Without it, a dominant network will remain dominant.

Saturday, November 20, 2010

A defining moment at Risky Business

Lord Ian Blair led London's Metropolitan Police through the investigations of the multiple bombings of July 7, 2005 and all that followed. His lessons about chain of command and the like are valuable to those who have to deal with disasters and emergencies. He presented this at the Risky Business conference in London this week.

Lord Ian Blair led London's Metropolitan Police through the investigations of the multiple bombings of July 7, 2005 and all that followed. His lessons about chain of command and the like are valuable to those who have to deal with disasters and emergencies. He presented this at the Risky Business conference in London this week.If you cannot view the video, click here.

BP Oil Spill at Risky Business

Here is a very good perspective on what went wrong to cause the explosion on the BP Deepwater Horizon drilling rig and the resultant oil spill, presented by Nick Coleman, VP in charge of Group Safety Performance Reporting until three years before the incident. He is now non-executive chair of the Risk and Safety Committee of Royal Brompton Hospital. He presented this at the Risky Business conference in London this week.

Here is a very good perspective on what went wrong to cause the explosion on the BP Deepwater Horizon drilling rig and the resultant oil spill, presented by Nick Coleman, VP in charge of Group Safety Performance Reporting until three years before the incident. He is now non-executive chair of the Risk and Safety Committee of Royal Brompton Hospital. He presented this at the Risky Business conference in London this week.If you cannot view the video, click here.

Everest disaster at Risky Business

Dr. Ken Kamler is a surgeon who also has served as doctor on some of the world's most daring expeditions, including the ill-fated climb up Mt. Everest in 1996. He told that story in this presentation at Risky Business in London this week.

Dr. Ken Kamler is a surgeon who also has served as doctor on some of the world's most daring expeditions, including the ill-fated climb up Mt. Everest in 1996. He told that story in this presentation at Risky Business in London this week.If you cannot see the video, click here.

Reconciliation at Risky Business

Jo Berry is founder of a charity called Building Bridges for Peace. Patrick Magee, PhD, was sentenced to life imprisonment for the Brighton Bomb which he set off as a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army in 1984. He was released in 1999. For 10 years he has worked for peace with Jo Berry, whose father he killed at Brighton.

Jo Berry is founder of a charity called Building Bridges for Peace. Patrick Magee, PhD, was sentenced to life imprisonment for the Brighton Bomb which he set off as a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army in 1984. He was released in 1999. For 10 years he has worked for peace with Jo Berry, whose father he killed at Brighton.They offered this discussion at Risky Business in London yesterday.

If you cannot see the vido, click here.

Friday, November 19, 2010

Sekou at Risky Business

if you can't see the video, click here.

Pedro Algorta at Risky Business

If you can't see the video, click here.

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Risky decision-making

The aim of this conference is to hear from some of the highest achievers in other high risk industries on the topics of risk, human factors, patient safety, teamwork, leadership, and improvement.

The presentations have been among the best I have heard anywhere. There are several I would summarize, but for now, please consider watching this one by Pat Croskerry, Professor in Emergency Medicine at Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Croskerry's exposition compares intuitive versus rational (or analytic) decision-making. Intuitive decision-making is used more often. It is fast, compelling, requires minimal cognitive effort, addictive, and mainly serves us well. It can also be catastrophic in that it leads to diagnostic anchoring that is not based on true underlying factors.

Why is it addictive? Croskerry describes the "cognitive miser function," a tendency to get comfortable with the form of decision-making that you find most used and useful.

The problem, of course, is that the overall rate of diagnostic failure is about 15%, and most of those diagnoses are made based on the intuitive approach. Not that the analytic approach is always correct, either. Indeed, in studies of factors contributing to failures to diagnose, cognitive errors alone or in part account for about 75% of the cases.

Croskerry thinks we need to spend more time teaching clinicians to be more aware of the importance of decision-making as a discipline. He feels we should train people about the various forms of cognitive bias, and also affective bias. Given the extent to which intuitive decision-making will continue to be used, let's recognize that and improve our ability to carry out that approach by improving feedback, imposing circuit breakers, acknowledging the role of emotions, and the like.

While you are at it, check out the video of this presentation by Duncan Murrell, who employs intuitive decision-making while photographing humpback whales -- sometimes in the middle of a feeding frenzy -- from a kayak in Southeast Alaska. (You can see the photographs up close here.)

If you can't see the videos, click here.

MLB praises Red Sox Scholars program

Major League Baseball announced today that the Boston Red Sox have been named the recipient of the inaugural Commissioner's Award for Philanthropic Excellence. Created by Major League Baseball and chosen by a Blue Ribbon Panel comprised of Commissioner Allan H. (Bud) Selig and MLB Executives, the award recognizes the Red Sox extraordinary charitable programs, run by the Red Sox Foundation, which have resulted in significant and sustained community impact.

Commissioner Selig presented the club with the award today at the Industry Meetings in Orlando, FL. . . .In singling out the Red Sox for this prestigious award, the Commissioner praised the depth of the Red Sox charitable programs and specifically the impact of the Red Sox Scholars program, the educational cornerstone of the Red Sox Foundation.

... said Commissioner Selig. "I congratulate the entire Boston Red Sox organization, and particularly the Red Sox Foundation, for their commitment to the future of hundreds of young people from the inner-cities of Boston."

... Each year, the Red Sox select 25 academically talented, economically disadvantaged Boston Public School students in 5th grade as Red Sox Scholars. Through the program, run by the Red Sox Foundation, the Scholars receive tutoring, mentoring, after school enrichment opportunities, summer camp assistance, and other leadership development activities. Red Sox Foundation staff members work with the Scholars intensively in 6th through 12th grades and each Scholar is awarded a $10,000 college scholarship redeemable upon graduation from high school with enrollment in an accredited college, and on condition of continued good citizenship. There are currently 200 Red Sox Scholars with members of the first class selected in 2003 now college freshmen.

The Red Sox Scholars program is presented by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), the Official Hospital of the Boston Red Sox. Over the years, almost 200 BIDMC physicians, nurses, medical technicians and administrators have been individually paired with the Scholars as Medical Champions. BIDMC also hosts "Shadow Days" for the Scholars each year, giving them an opportunity to visit the Neo-natal Intensive Care Unit, the Simulation Center and Skills Lab, and other parts of the medical center to be exposed to a variety of careers in medicine.

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

ED report card

Here is the trend in our place. Each year we admit about a dozen residents. Note the growth in applicants year to year in the top chart.

And the chart underneath shows their performance on the standardized examination. Nicely above average year after year for all three classes of residents.

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

The US dialysis program -- How good and how bad?

A recent article in ProPublica by Robin Fields contains a number of strong criticisms of the US dialysis program for people with kidney disease. Here's an excerpt:

Now, almost four decades later, a program once envisioned as a model for a national health care system has evolved into a hulking monster. Taxpayers spend more than $20 billion a year to care for those on dialysis -- about $77,000 per patient, more, by some accounts, than any other nation. Yet the United States continues to have one of the industrialized world's highest mortality rates for dialysis care. Even taking into account differences in patient characteristics, studies suggest that if our system performed as well as Italy's, or France's, or Japan's, thousands fewer patients would die each year.

NPR's Terry Gross recently interviewed both Robin Fields and Barry Straube, Chief Medical Officer for Medicare. The interviews are worth hearing or reading. Here's an excerpt from Dr. Straube's interview:

I believe that Robin's article, although pointing up some very important issues that this agency and the Department of Health and Human Services is aware of and trying its best to fix, that it overstates significantly the degree of the problem out in the real world. It makes it sound like any dialysis unit that a patient would walk into is subject to these problems and that's simply not true. The vast, vast majority of the units are not as described in the several examples, which are completely true examples but not illustrative of most dialysis units.

I think my main quibble with the article is that it sounds as though one would not want to have dialysis in the United States. This is a life-saving treatment that the vast majority of people are being treated very well in very clean facilities that hopefully make very few mistakes. And the examples there are not indicative of most dialysis units.

I conclude, having read and heard both, that there are elements of truth in the article about this kind of care and need for improvement. However, the magnitude of the problem seems to me to be less than reported. I welcome your thoughts.

Monday, November 15, 2010

Middle school explorers in BIDMC Labs

Four students from the William Barton Rogers Middle School in Hyde Park spent a morning at BIDMC with Parameswary Muniandy, PhD, a pathology research fellow studying brain cancer. “Early exposure to science and how research works really helps them develop an interest in science,” said Muniandy. She helped the students feel like real researchers by putting on lab coats and gloves.

You can watch the excitement in this video. If you can't see the video, click here.